“We pray that you strengthen our relationship and that you help us to understand each other and to love each other. Amen.”

This is how Iris and Genea Richardson begin every morning — hand in hand, and Ricky Ricardo (their rescue dog) in lap — with a prayer, together. But for the last 18 years of their lives, they prayed alone.

At the age of 17, Genea was sentenced to 26-years-to-life in prison for robbery and first-degree murder. During this time, her mother Iris was left battling depression, had attempted to commit suicide four times, experienced the death of her fiancé, and was homeless for four years.

Separated by metal bars and distance, the two still prayed every morning.

Genea spent the first six years of her time in county jail. There, her contact with her mother was limited to choppy phone calls and occasional in-person visits. But all contact was lost when Genea was moved to Central California Women’s Facility — where she lived in a cell with seven other women for the next 12 years. During Genea’s time in the prison, a friend who was being released made her a promise: to find her mother. They successfully reconnected months after.

Genea had also filed an appeal in her case. And in the summer of 2020, she was released.

“We don’t have much experience through those years [in prison] to get a real picture of what life may look like. So it’s kind of shocking when you come home and things are a little different from what you envisioned,” Genea said.

After time behind bars, it can be overwhelming to reenter society — especially when imprisoned at the age of adolescence. Many previously incarcerated individuals report feeling frustrated with adapting to technology, finding a job, paying taxes or even using social media. So much can change over the span of just five to ten years that it can feel like one is entering into an entirely different world once they are released.

“When you’re at your lowest point, they incarcerate you and they separate you from society. They separate you from experiences,” Genea said. “So, you’re broken and you’re hurting, and you’re at your lowest point. This cannot possibly be conducive to any type of growth or healing in your life.”

Genea turned to poetry to process her emotions while adjusting to life in prison.

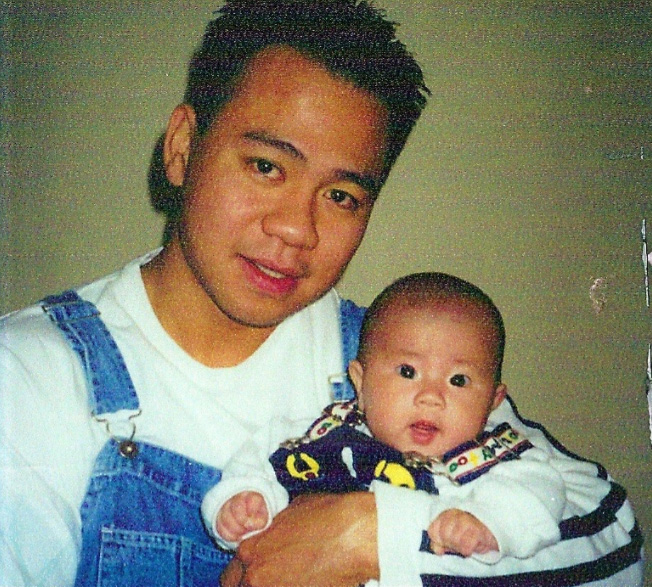

Iris, Genea and Ricky, their support dog.

Poetry also helped Genea to see more than just herself. She began to understand the troubles that her actions were putting upon others, like her mother.

“I would think about my mom and the burden that came to her because of me. I didn’t see this before, but I now see that my mom is the face of so many mothers and the burdens they carry. I see the tears of many mothers in my mom’s tears. I see the heartache of many mothers in my mom’s heart,” Genea said.

Returning to her mother after nearly two decades of being apart, Genea says they are making up for the lost years with Sunday dinners, Christmas movies, trips to the grocery store, and even with the bickering. “When she went in, she was a child. She’s come out as a woman and that’s kind of hard to accept because I still consider her as my child,” Iris said.

At times, Genea says she feels the stereotypical mother-daughter roles have been reversed because both were deprived of tenderness and care for so long. As a 39-year-old woman, Genea is relearning what a healthy mother-daughter relationship looks like.

“I went into prison during one stage of my life, and I came out at a very different stage and age. We didn’t have the opportunity to fully develop our relationship together so there’s a lot that’s missing,” Genea said. “How much should my mother be doing for me? How much should she not be doing for me? We’re just trying to pick up the pieces and learn our roles.”

Genea now strives to be a voice for women’s reentry. She does this through her work with Huma House — a nonprofit reentry program that works to give a voice back to previously incarcerated individuals. As the Director of Gardening, she leads soil therapy programs, restorative justice classes and radical listening workshops.

“The goal is to empower women in these gardening and landscaping experiences to get them to the core of themselves, to get them to the soul of themselves by putting their hands into the soil and hoping that they receive healing,” Genea said. “We correlate that healing with the garden — that’s our soul. We are gardening our souls.”

Genea and Iris currently live together in a 500 square foot Los Angeles studio apartment—one that is not much bigger than the prison cell Genea spent so much of her life in. But their humble space is a reflection of their growth during this new chapter in their lives.