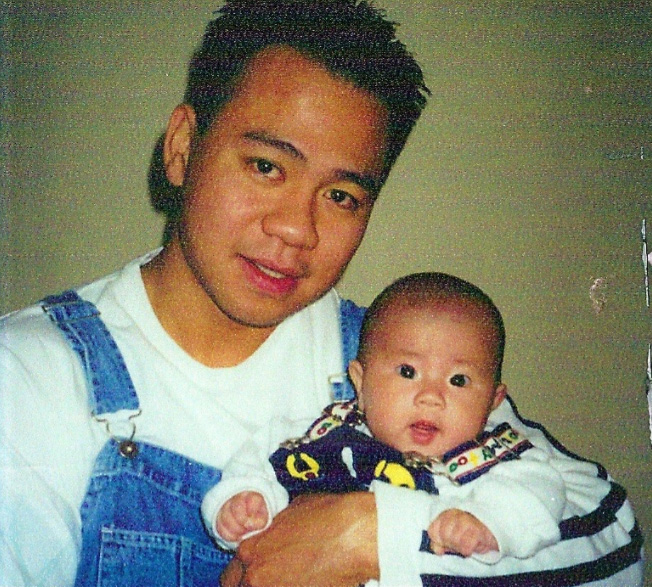

“[That day] stands out as a pivotal day that signaled the beginning of the end of a cycle of violence that had infected the fabric of my family for generations,” said Samuel Lazalde, who spent years in and out of juvenile detention centers because of his gang involvement.

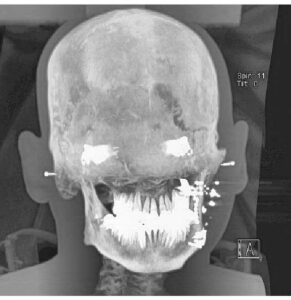

X-ray of Samuel Lazalde’s bullet wound.

A bullet fragment was shot through Lazalde’s face, exiting his head behind his left ear, while several other fragments shattered his jaw bone, salivary gland and other muscles, ligaments and tendons. His friend in the passenger was also shot multiple times.

Two weeks later, Lazalde awoke from a coma with his jaw wired shut and held together by a mouth full of screws.

In a system where youth in poorer communities are overlooked and use gangs as an outlet to feel a sense of belonging, Lazalde felt he had no choice but to resume his previous life involved in criminal activity once discharged from the hospital.

He went back to his gang-related friends.

“While the behavior of the gang offers dysfunction and danger, on another level it offers a place to belong and be recognized,” Lazalde said. “Unfortunately, the current system lacks the insight and fortitude to offer solutions that counter the inevitability of entering the prison system.”

Months after being shot, 22-year-old Lazalde – surrounded by his younger, teenage friends – felt overwhelmed realizing the boys were heading in the same direction, continuing the cycle of at-risk youth going down the wrong path.

“I knew that the only reason those boys were there with me was because I was there,” Lazalde said. “I understood my place in their lives and realized the power that I had to move their lives in a different direction than where they were going.”

After that moment of clarity, he concluded that education was necessary to finally break the cycle that has engulfed his community for decades.

Lazalde was also president of CSUN’s Matadors Boxing Club.

After graduating, Lazalde enrolled in the University of Southern California’s School of Social Work in order to pursue his goal to assist youth in finding outlets and refraining from getting involved in violence.

Today, he serves as the Director of Programs for Neutral Ground, a company Pastor Nati Alvarado started in Santa Ana, CA.

Neutral Ground offers services in prevention, intervention and mediation for students and families. It also provides boxing classes.

Lazalde uses his past experiences to help young teens from getting pulled into the school-to-prison pipeline. He employs restorative practices to create an open space for students and provide an outlet for those in communities impacted by gang activity.

“I have been a catalyst for change, actively working to strengthen community resiliency to the influence of gangs and gang violence,” Lazalde said. “Learning how to change the social fulcrum to bring about critical changes on a local, state and national level feels like the direction to which I’ve been called and where I can make the biggest difference in the lives of those who can most benefit from it.”

Lazalde blends restorative practices with boxing classes at a church in Santa Ana.